Pregnancy

Article curated by Rowena Fletcher-Wood

There are many unknowns when it comes to pregnancy, and many accepted phenomena are still unexplained, or simply attributed to "hormones" or "the placenta" (a complex and poorly understood organ!)

Morning Sickness

Animals also get it. In a study of 202 female rhesus monkeys, it was found they systematically rejected foods or certain foods both whilst they were ovulating and in early pregnancy, peaking around week 5[1].

There are three main theories for why women experience morning sickness:

1. Prophylaxis – the embryo protects itself by making the mother averse to potentially dangerous foods. In particular, women experience aversions to strong-tasting vegetables, caffeine and alcohol, which are potentially abortifacient, and, even more strongly, to animal products such as meat and eggs, which carry a high risk of parasites and pathogens. One cross-cultural study found 7 traditional societies that had no history of morning sickness, and noted that they were significantly less likely to include animal products in their diets than 20 other traditional societies that had[2].

Women who feel sick also have a higher probability of a healthy pregnancy, and lower probability of spontaneous abortion. However, this does not explain Hyperemesis Gravidarum, which makes the woman so sick she is at risk of dehydration, malnutrition, and even death.

2. By-product – sickness is a nasty side effect that serves no direct purpose, caused by mother and baby competing over essential resources or the hormones associated with viable pregnancies.[3].

3. Social indicator – letting others know a woman is pregnant to ward of sexual partners and increase social support (there seems to be nothing in the literature at all about this!).

During the critical first trimester, most women get sick and go off bitter things, including coffee. This has completely messed up medical research into the effects of caffeine, because it’s difficult to untangle high consumption from lack of sickness. Some research suggests excessive caffeine consumption magnifies other negative effects[4].

Learn more about Alcohol and Caffeine (Things We Don’t Know about Pregnancy Series #9).

Morning Sickness

Advice on relieving morning sickness is also controversial. Many tricks don’t have an explanation behind them, such as ginger, used for centuries as a sickness remedy, and still unexplained – or sea bands, which apply acupressure, an eastern medical technique that currently remains unsupported by scientific evidence. Another controversial remedy is vitamin B6, which comes with both studies showing no effect[5], and studies showing effectiveness in treating morning sickness[6].

Learn more about Morning Sickness (Things We Don’t Know about Pregnancy Series #1).

The Thalidomide Scandal

In 1953, thalidomide was prescribed for morning sickness, but then over 10,000 babies were born with deformities.

There are more than 30 proposed mechanisms for how thalidomide caused these birth defects, and in fact, it looks like more than one could be true. Mechanisms include causing mutations in DNA and cartilage, interfering with neural networks, generating reactive oxygen species (which accelerate cell ageing in the body), and inhibiting some proteins[9]. It is also antiangiogenetic, which means it stops the development of new blood cells – exactly what happens when the placenta is forming between 6 and 12 weeks of pregnancy.

We do know that thalidomide binds to a target protein called cereblon, and it was this binding that eventually led scientists to prove only left-handed thalidomide caused birth defects: because they bind differently: x-rays and electron mapping showed the left-handed version binds easily, but the right-handed version is twisted and easily falls off.

To perform these experiments, scientists doped thalidomide with deuterium to stop them from interconverting[10].

Scientists first suspected only one form of thalidomide caused defects because many naturally occurring biological molecules such as proteins and sugars are left-handed only – although we don’t know why. Some scientists believe that the bias towards one chirality or the other is purely random. Other scientists, who subscribe to the theory that life on Earth was seeded from outer space, have proposed that polarized radiation bombarded the asteroids that brought the building blocks of life. In tandem, the body has developed key enzymes and receptors that only fit left-handed sugars and amino acids. Right-handed versions either do nothing – simply diluting the effect of the left-handed molecules, or they do something different… and that could be anything. We don’t know, and we don’t know how to predict where they might bind or react in the body!

However, scientists still can’t say for certain whether right-handed thalidomide is safe. Not only does it interconvert with left-handed thalidomide, but it breaks down in the body – either by metabolism or by hydrolysis – and some of the products of these reactions are also thought to be dangerous[10].

The birth defects of thalidomide were first observed statistically – because 20% of “thalidomide babies” had deformities, rather than 1.5%. However, years later, higher than usual rates of dyslexia, autism, or epilepsy were also observed. Medical professionals think that thalidomide taken later in pregnancy may cause brain damage, and these conditions could also be associated with late pregnancy consumption.

Why timing effects the kinds of birth defects caused by thalidomide, we don’t know. If taken very early, it seems to cause miscarriage; if taken between 20 and 36 days post ovulation (3-7 weeks, when morning sickness is most common), it causes physical deformities, and after that, brain damage.

Learn more about The Thalidomide Scandal (Things We Don’t Know about Pregnancy Series #10).

Pica and cravings

Along with sickness, many pregnant women experience cravings. Medical advice is to follow cravings, which may signal the need for certain nutrients. At the extreme end, some women suffer from pica, a craving for non-food things like dirt. Many crave ice cubes – which is directly linked to iron deficiency[11]; however, research has shown that pica sufferers with low iron do not necessarily crave iron rich foods – scientists can’t explain why.

Some women experience a persistent metallic flavour in their mouth (dysgeusia). Dysgeusia can stick around, fade away, or come and go throughout pregnancy, including after birth: the reasons why are unknown. Dysgeusia might happen to push women towards avoiding risky foods – but the taste persists even with “safe” foods. Or it might serve to drive a woman to eat things with trace salt elements in them, like calcium, sodium and iron. Alternatively, it could just be a side effect, and serve no biological purpose.

.jpg)

2

2Can you alter your baby’s tastes by what you eat when pregnant? Scientists think you can[12]. Afterall, babies tend to be happy with the food from the culture they belong to (and this makes evolutionary sense). Vegetarians find meat unpleasant, the Japanese like all things fishy, and some cultures are much happier with hot and spicy foods than others.

Although not all flavours carry through amniotic fluid or breastmilk, certain distinct flavours such as carrot, vanilla, mint and garlic do, and can even be detected as little as half an hour after eating by adults smelling them!

However, other effects, like genetics, interest in food, texture of the food, and how easy it is to pick up will also come into play, making baby feeding hard to assess. Food preferences are a complex interplay of biological, social, and environmental factors.

Learn more about Language of Smell.

Menstruating when pregnant

Morning sickness is a common symptom of pregnancy, but traditionally, a woman twigs she is pregnant when she misses a period, but this doesn’t happen to everyone. Some continue having “periods” for one, two, or more months. Whilst they are not truly menstruating, doctors can’t explain every bleed. Common explanations are implantation bleeding (when the embryo embeds into the uterus lining), subchorionic haematoma (where blood collects between the placenta and uterus lining), or miscarriage. Minor causes might be tears, inflammation, or infections. Around One in five women experience some kind of bleeding during pregnancy[13].

Cryptic pregnancies

Unlikely though it seems, 1 in every 475 pregnancies is “cryptic”, which means they go unnoticed by the mother, sometimes until labour. How does that even happen?

Scientists have found some links to psychological disorders and social pressures like unsuitable circumstances (e.g. women in the military), but somatic denial can’t explain cryptic pregnancies altogether.

Biological factors include masking conditions, such as Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome (PCOS), which reduces fertility, creates fluctuating cycle lengths, and hormonal imbalances, or the menopause, which causes changes in weight, suppressed menstrual cycle, and hormone imbalances; birth control, especially hormonal birth control; or stress factors such as high levels of exercise, stress, or being underweight, which can lead to disruption of the menstrual cycle.

Symptoms are also reduced in the case of cryptic pregnancies. 74% of women with cryptic pregnancies experience pseudomenstrual bleeding[14] and lack of morning sickness; foetal movements may be mistaken for gas, and abdominal growth is reduced, with the foetus sitting closer to its mother’s back, and often underweight.

Tests that should be positive can also come out negative. A home pregnancy test and even blood test can fail like this when hCG levels are low, which they typically are in cryptic pregnancies. 12-week ultrasounds can fail to detect a living foetus if its implanted in the wrong or an unusual place, the uterus is unusually shaped, or the ultrasound device or technician make a mistake. Uteruses that are tilted towards the back (uterine retroversion) or heart-shaped (bicornuate) can conceal a pregnancy or make a foetus hard to see. Scar tissue can also get in the way, such as marks from a caesarean or tummy tuck.

There are three main biological theories behind cryptic pregnancies[15].

- Cryptic pregnancies may be a nonadaptive outcome of parent-offspring conflict – favouring the mother by giving her a bigger share of food, increasing her mobility, and making her less mate-dependent. This puts the foetus at risk, but the mechanism may have survived because babies born via cryptic pregnancies don’t seem to have anything else wrong with them except being undersized. The theory suggests this outcome is genetically driven.

- Cryptic pregnancies may come about when the mother’s body tries to spontaneously abort a foetus, either because it’s low quality or because she can’t produce enough hCG to support it. However, if the foetus can make just enough hCG, it can grow despite maternal rejection and her own biological investment is suppressed.

- Alternatively, a cryptic pregnancy could be an example of forced cooperation between mother and foetus under psychosocial stress. That is, the mother’s investment in the foetus is reduced, maximising her chances of surviving the stressful situation and therefore carrying the baby to term, at the potential expense of its overall health. These theories may not be mutually exclusive.

- Confounding factors that contribute to the likelihood of a caesarean, like an older mother, defective placenta, or premature baby.

- Use of antibiotics during the operation.

- 1/3 the rate of gestational diabetes

- 2/3 the rate of preeclampsia

- 1/4 the rate of low back pain

- Lower chances of deep vein thrombosis

- 1/3 the rate of epidurals

- 1/4 the rate of induced labour

- 1/4 as many caesarean sections

- Lower chances of umbilical cord tangling

- Dizziness

- Headache

- Extreme thirst

- Swelling

- Chest pain

- Vaginal bleeding

- Contractions

- inhibiting the development of the nervous system

- altering foetal DNA or gene expression

- effecting heart rate and cortisol levels

- producing reactive oxygen species, which accelerate cell ageing and death

- upsetting glucose, protein, lipid and DNA metabolism

We don’t know how long cryptic pregnancies last because the women who get them didn’t know about it at the time. However, some think they last longer or shorter than recognised pregnancies. There are good reasons for these theories.

The theory that they last longer is based on the idea that hormone concentrations are lower, slowing foetal growth and so demanding a longer term. Others think that lack of prenatal care and pregnancy-conscious dietary choices increase the odds of a preterm birth.

Check back for our dedicated blog post on cryptic pregnancies soon!

Phantom pregnancies

Sometimes, like in many cryptic pregnancies, there is no medical evidence of pregnancy, but the woman still labours under the impression that she is pregnant. This is known as pseudocyesis, or delusion of pregnancy, or phantom pregnancy. Phantom pregnancies can also occur in males, and can last significantly longer than recognised pregnancies, some for many years. We don’t know why phantom pregnancies come about, but it correlates strongly with the post-menopause period and weakly with psychiatric disorders including schizophrenia, other psychotic disorder, mood disorders and organic brain disorder [16][17][18][19].

Superfetation

Superfetation – the phenomenon of becoming pregnant whilst already pregnant – is reported in humans, hares, badgers, mink, panthers, buffalo, wallaby, rats, mice, rabbits, horses, sheep, kangaroos, sugar gliders and cats. But much of the evidence is dubious, and remains controversial. The only agreed incidents seem to be documented in fish that carry their young – the poecilid and zenarchopterid.

Superfetation shouldn’t happen. Once conception has occurred, hormones are released that prevent further ovulation, and a mucus plug blocks up the womb. It’s usually diagnosed when “discordantly developed young” are seen with separate amniotic sacs that can’t be explained any other way, but there have never been discordantly developed young documented that are more than a few weeks apart in growth.

Critics argue that these superfetation-like pregnancies have other origins, such as placental insufficiency, twin-to-twin transfusionembryonic diapause[20].

Alternatively, it may be a real reproductive strategy to maximise their number of offspring. But if it is, it opens up more questions than it answers, including why it’s so rare and what provokes it when it happens, how it evolved, how the endocrine system regulates it, and how the maternal and foetal microbiome and immune systems behave.

Scientists have attempted to classify superfetation into three groups[21]:

1. Superfertilisation (or superfecundation) describes the fertilisation of two or more ova by two different males. It happens when there are two or more eggs released together in one cycle, and two sexual acts within the fertility window. The result is twins babies with different biological fathers.

2. Superconception is what scientists think happens in “permanently pregnant” hares[22]. Towards the end of pregnancy, the female ovulates and mates. Researchers have shown this ovulation using high-resolution ultrasound imaging to show fresh corpora lutea (cysts that form when eggs exit the ovaries). After giving birth, the egg then implants in the now-available womb.

3. In superfetation proper, a second ovulation cycle, or several subsequent ovulation cycles, happens during pregnancy, and a second foetus or litter is conceived. This produces two babies or litters, the younger of which is at risk of premature birth. This is most likely to happen when the female has two uteruses, or if implantation of the first embryo is delayed, so cycle-suppressing hCG hormones come too late. In humans, superfetation proper generally happens after fertility treatment, when a woman’s natural cycle isn’t sufficiently suppressed[23].

Check back for our dedicated blog post on Superfetation soon!

Sleep

Most studies conclude that concerns about labour or becoming a mother drive nightmares during pregnancy, but these don’t explain all dreams, including the commonly reported sex dreams!

Other scholars think rising progesterone may be responsible for sleepiness and dream intensity. Increased tiredness increases the volume of sleep and so the volume of dreams. Pregnancy discomfits also break up the rhythm sleep, meaning you wake more and recall more. We can’t ignore these physiological factors (hormones and discomfits), otherwise we’d expect to see the same kinds of and vividness of dreams in (involved) expectant fathers. Some expectant fathers do report increased dreaming and more vivid and anxious dreams, but not all or as much.

Although they’re not sure why, some researchers have linked poor sleep to longer and more difficult labour and delivery, with women sleeping less than 6 hours a night 4.5 times more likely to undergo caesarean operation. Others found that shorter and easier deliveries were linked to labour nightmares, and hypothesised that this was because women were “practising” in their dreams!

3

3The thalidomide scandal highlights an important medical problem: that women, along with other marginalised categories such as ethnic minorities and the elderly, are still massively underrepresented in clinical studies[24][25][26]. This means there are many unknowns about women’s health from sleeping disorders to heart attack symptoms, leading to misdiagnosis, mis-dosage, and severe health risks, that make women more likely to die of preventable medical conditions. However, this has been recently recognised and many scientists are working to try to effect change.

2

2

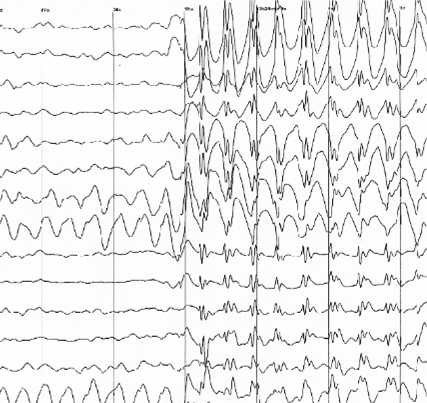

Using these methods, REM (rapid eye movement) sleep sleep is detected from around 7 months, when the brain cycles in and out of restful and REM sleep every 20 to 40 minutes and the foetus sleeps 90% of the time. Very little is known about foetus sleep before this. However, new research into lambs has shown that foetuses enter a dreaming-like brain state weeks before REM sleep starts[27]. As well as learning more about sleep, this study could help us figure out how the brain develops and when it is most at risk.

When a baby starts to move, its motions are involuntary, but they soon become voluntary – around 16 weeks. Nevertheless, the baby is mostly sleeping, and that means many of the motions are instinctive responses to outside pressures – and possibly, although we don’t know, dreams (it’s believed that adult-like dreams (develop around age five. One thing we do know is that unborn babies do not have their limbs paralysed when they sleep to stop them from acting out their dreams, which happens to adults, and leads to the phenomenon of sleep paralysis.

Alas, there’s no evidence the movements and routine of unborn babies codes for the movements and routines of born ones, although lots of anecdotal information says there might be.

Learn more about Sleep Paralysis - A Ghost Story.

Opinion is divided when it comes to whether foetuses sleep more at night or day. Until 3 months old, they don’t produce their own melatonin – so rely on mum. But does it work to make babies sleep? Many babies are soothed by their mother walking, and this persists after birth, with motion such as rocking sending them to sleep, whilst stillness makes them wake up.

Another area of research is the relatively un-navigated territory the relationship between foetal health and maternal sleep. Some studies think that the mother can influence her child’s health by sleeping well when she’s expecting, but the cause-effect relationship between impaired sleep and infant health is a difficult web to untangle!

Learn more about Foetal health and maternal sleep.

Skin

Learn more about Bizarre symptoms (Things We Don’t Know about Pregnancy Series #3).

Weight

In the US, health professionals obsessively monitor women’s weight whilst pregnant. However, the correct amount of recommended weight gain during pregnancy is debated scientifically[28], and the weighting process is often counter-productive because it makes women worry.

Weight gain goes towards growing the placenta (1.5 pounds), amniotic fluid (2 pounds), increased tissue masses (4 pounds), extra fluids (4 pounds), increased blood volume (4 pounds), and, of course, the baby (7.5 pounds). A further 7 pounds is stored nutrients, including fat, believed to be a vital resource during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Scientists don’t know exactly how this happens – only that it’s controlled by hormones.

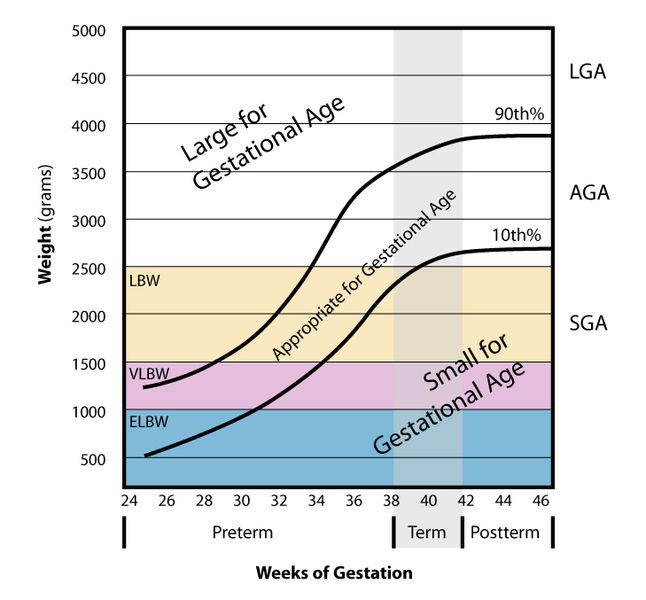

Because baby growth is affected by what you take in, weight affects baby size. Very large or very small babies are at risk of more complications, especially small for gestational age (SGA) babies. SGA babies carry a risk of cardiovascular, respiratory and digestive complications, whereas SGA (large for gestational age) babies cause birth problems – usually leading to caesarean[29]. Or, in other words, small is bad for baby, big is bad for mother.

Statistical analyses of competitive athletes (not climbers) has shown that women who are extremely fit are less likely to have overweight babies and equally likely to have underweight babies, with a slightly lower average weight. Since women who are very fit are less likely to be overweight, and overweight women tend to have heavier babies, this could just be a biased sample effect.

But weight gain during the pregnancy is not the only thing that affects baby weight. Even more important is when the baby is born – early, late, or close to their due date, any conditions the mother may get like gestational diabetes, and her starting weight.

Over- and underweight women can be at increased risks of pregnancy complications. However, overweight and obese women are still recommended to gain weight during pregnancy – just less. Being obese carries a chance of reduced fertility, higher incidents of miscarriage, stillbirth, birth defects, gestational diabetes, preeclampsia, sleep apnea, blot clots, and a tricky delivery/recovery. It can also complicate spotting birth defects. Being underweight carries the risk of premature birth and SGA at birth – and so risk of cardiovascular, respiratory and digestive complications in the newborn.

Learn more about Weight (Things We Don’t Know about Pregnancy Series #2).

Microbes and genes

![Baby By Beth [CC BY 2.0], via Flickr](/img/sci/baby.jpg)

Learn more about Microbes and genes.

2

2Caesareans

Are caesareans risky? Maternity mortality rate for caesarean section is now only 3 times that of vaginal births[35], but this may be because a number of caesareans are only carried out in emergencies. Caesareans may also reduce the risk of complications in some cases: for women who have previously had a caesarean section, choosing an elective one for a subsequent baby over a vaginal birth reduces the risk of complications or consequential health problems (such as womb damage) from 1.8% to 0.8%[36]. Overall risk remains minute.

Regardless of whether elective or emergency, a review of 20 million births across 61 studies has shown that babies born by caesarean are a third more likely to develop autism and a sixth more likely to develop ADHD[37]. Possible explanations include:

But it seems unlikely it is linked to mode of delivery.

Studies have shown that parents recognise their own baby’s cries above those of others and are more responsive to their needs due to an amplifying effect of the hormone oxytocin[38] [39]. The effect, however, is not as strong if the baby is delivered by caesarean section[40]. We’re not sure why.

Interestingly, fathers are equally good at recognising their own baby’s cry as mothers, but, for some reason, they are less sensitive to oxytocin and giving them more doesn’t seem to increase their sensitivity to baby cries[41][42].

Exercising whilst pregnant

Exercise is good for you – but how much exercise is good for you when you’re pregnant? Recommendations are ever-changing, and for some sports, such as climbing, there are no controlled studies for performing whilst pregnant.

However, one literature review found that women who exercised at high intensity had a range of reduced pregnancy symptoms, including:

They also showed a better ability to tolerate heat stress, and shorter, easier labours, including:

It even lowers the risk of ‘baby blues’ and postpartum depression.

Because of these general benefits, it’s impossible to say whether certain exercises, such as prenatal yoga, are in any way beneficial. Studies are not only performed on women who are already fitter than average, but also tend to be performed by people already biased towards yoga, and involve only small groups of women (such as 25).

However, during pregnancy, the body changes and remodels itself; the hormone relaxin relaxes ligaments and loosens joints, making injuries like dislocations and pulled muscles more likely. Centre of gravity shifts, upsetting balance, and oxygen increases, with an extra 20% of blood flowing, which can make a pregnant woman’s blood pressure drop, leaving her more prone to dizziness. As such, pregnant women should avoid any exercise that might make them dizzy and so fall over (which could injure her or her baby), including lying on their back for prolonged periods. This is why so many yoga positions are contraindicated, such as inversions, along with the more obvious sports such as skydiving and horseriding. Other positions, like standing twists, can put also pressure on the abdominal cavity, which, in the worst case scenario, could lead to placental abruption. Similarly, other high impact sports like kickboxing, judo or squash are not recommended, where the bump could get hit. However, the risks of these exercises are minimally studied, and advice is simply not to do them.

How much exercise to actually do varies person to person.

Beginners should pick whole body sports that don't involve moving in any very new way and so minimise risks of injury, like walking, swimming and running, for 150 minutes or so a week. However, for fitter women, this would involve reducing exercise: experts recommend you carry on with what you’ve been doing (climbing, pilates, badminton…) and tell your instructor you're expecting in case anything needs to be adapted.

In the past, pregnant women used to get told not to let their heart rate go above 140 beats per minute, but this arbitrary number has been slacked off as it doesn't really tell us much about safe limits. Instead, look out for signs that you're unwell, including:

Or, on the more worrying end;

Scientists are investigating how, but it seems getting too hot and staying too hot for prolonged periods has been linked to malformations and birth defects in unborn babies, especially during the first trimester. This has led some people to avoid exercising hard. However, you’d have to run very fast for at least a couple of hours to get your body temperature near the danger zone. Studies on competitive athletes who work out at above 90% their recommended maximum heart rate have so far shown no increase in birth defects. “Hot yoga”, “hot pilates” and saunas, however, are deemed hot enough to pose some risk.

Learn more about Exercise (Things We Don’t Know about Pregnancy Series #8).

Miscarriage

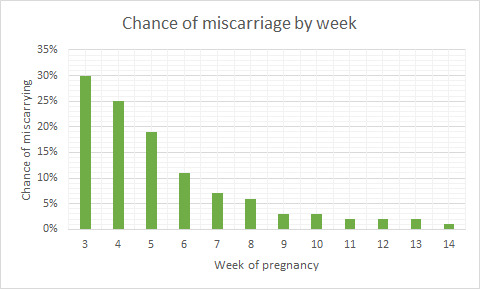

Miscarriage is a common medical complication that leads to the loss of a pregnancy before 23 weeks, and affects 1 in 4 women during their reproductive lifetime. Most miscarriages make themselves evident with symptoms including abdominal pain, discharge, and vaginal bleeding. These symptoms can abate, or progress to the expulsion of the foetal tissue after days or even weeks. However, once it’s started, we don’t know any way to stop it: nature simply runs its course. Sometimes the uterus doesn’t empty out properly, and an operation has to be performed called dilatation of the cervix and curettage of the uterus (or D & C).

There are five main reasons for a miscarriage:

(i) genetic or chromosomal abnormalities, where a foetus inherits a faulty gene, or copying errors occur when cells are dividing early on[43].

(ii) lifestyle factors such as smoking, drinking, obesity, or malnutrition

(iii) health conditions like uncontrolled diabetes, thyroid disease, high blood pressure, food poisoning, infections (especially in the uterus), trauma, or hormonal disorders – or the use of non-compatible medications.

(iv) mis-implantation – when an egg implants outside the uterus (usually on the walls of the fallopian tube). This is a medical emergency because the placenta develops a complex network of blood vessels between the mother’s tissues and the baby’s – meaning that when it peels away at birth, massive internal bleeds can happen if it’s not attached to the uterus, a muscle that contracts to stem the bleeding. Around 1 in 80-90 pregnancies are ectopic in the UK.

(v) placental problems: which can be affected by blood disorders, trauma, or multiple pregnancies, amongst many things. Amongst things that can go wrong, insufficiency (not passing the baby enough nutrients) and abruption (coming off the uterus wall too early) are linked to miscarriage.

Molar pregnancies, for instance, are non-viable pregnancies where cells develop to look like a bundler of fish eggs, but don’t form a foetus. No one knows why they happen, but they have to be surgically removed – occasionally by full hysterectomy. For a molar pregnancy to happen, there must something wrong with the fertilised egg, such as missing a nucleus – but not all non-viable eggs lead to molar pregnancies.

Molar pregnancy can spread deeper into the uterine tissues, known as an “invasive mole”, developing into cancer in 2-4% of cases. Younger (under 20) or older (over 35) women are more likely to suffer molar pregnancies, women who suffer nutritional deficiencies of protein, folic acid, or carotene, or women who’ve had a molar pregnancy before – we don’t know why.

Learn more about Silent Miscarriage (Things We Don’t Know about Pregnancy Series #11).

When the amniotic sac that usually contains a foetus develops without the foetus in it , this is known as ablighted ovum or anembryonic pregnancy. The empty sac means that the fertilised egg never implanted, or didn’t develop properly, and instead got reabsorbed back into the uterus. Whilst this happens early on, if the placenta continues growing, it makes all the hormones associated with pregnancy anyway, masking the loss. Normal pregnancy symptoms progress, and the sac often has to be removed surgically. Scientists don’t know what causes a blighted ovum, but it could be linked to complications chromosome 9 and is more common if the parents are biologically related.

Read more about miscarriage and ongoing research on the topic here.

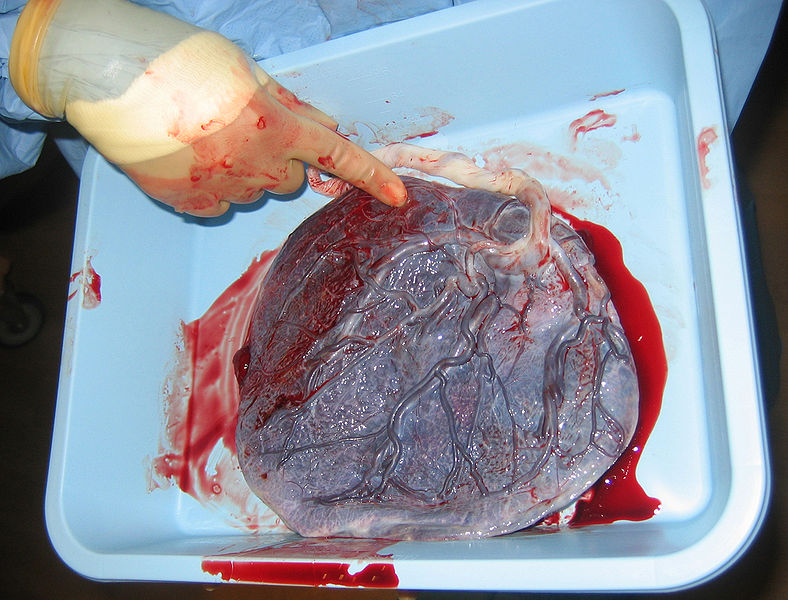

The placenta

The placenta is a complex and poorly understood organ. A two-sided disc, one side develops from the mother’s tissues 7-12 days after conception and sticks to the womb, and the other forms 17-22 days after conception from the blastocyst that starts off the foetus, once it has connected up with the mother’s blood supply. Scientists are still studying how the placenta forms.

Mostly when something foreign enters a woman’s body, her immune system attacks it. Scientists are still trying to uncover why she doesn’t also kill off a foetus. Understanding the process could reduce miscarriage frequency (~10% of pregnancies). The placenta is believed to be instrumental in conveying “immune privilege” to the foetus. Amongst its many activities, the placenta secretes neurokinin B – the chemical used by parasitic nematodes to avoid detection by the immune system of their host!

However, it’s not the only time when genetically different cells have been found living inside our bodies. Because some cells cross the placenta, mothers keep some of their babies’ cells, and their offspring carry some of their mothers. Cells may also be exchanged between unborn twins, and younger siblings may carry some of their older brothers and sisters. What these microchimeric cells do and how benign they are remains unsolved, but they have been implicated in brain health: fewer are found in the brains of women who get Alzheimer's[44][45].

One Nature study suggested that schizophrenia could develops during pregnancy when “schizophrenic genes” are turned on in the placenta[46]. These findings are the first to link early life complications, genetic risk and mental health.

At the end of its life cycle, the placenta starts to break up. For placenta-sharing twins, this can sufficiently limit their oxygen and nutrient supply that doctors will induce the mother early. We don’t know why it breaks up early, but it might help detach it from the womb wall so that it can be expelled in the “third stage of labour”. During this stage, women are often given an oxytocin injection their thigh to stimulate contractions and help expel the placenta. For some reason, this reduces postpartum bleeding, but scientists think there may be conflating adverse effects, and more research is needed[47].

After birth, the cord to the placenta is cut. However, some research suggests it would be better to wait, allowing the baby absorb nutrients from placental blood that could help it adapt and decrease chances of anaemia[48]. Scientists are interested in what special qualities placental blood may have. Others have suggested delaying cord cutting may be linked to increased risk of jaundice[29].

We still don’t know how the placenta controls what can and cannot pass. It’s possible viruses can get through where bacteria can’t because they’re smaller. Yet the placenta collects and stores some chemicals, including medications from the mother’s bloodstream. If doctors could understand what triggers the storing mechanism, they could design medications that could treat the mother and not affect the baby.

Modelling the placenta is hard because placental cells do not spontaneously grow into a placenta, and trophoblast starter cells do not divide. Scientists have managed to get some growth using a microgravity bioreactor system to model shear stress and rotational forces.

Towards the end of pregnancy, the placenta passes antibodies from the mother to the baby that weren’t allowed to transfer earlier, conveying passive immunity to the baby for about 3 months. But only some kinds of antibodies can pass – ones acquired a while ago. Diseases caught and fought off whilst pregnant don’t transfer!

For more about the placenta, see our blog post on the subject.

Toxoplasmosis

One such disease is toxoplasmosis, contracted from toxoplasma gondii, a protozoan parasite that will infect a third of people over their lifetimes.

Women who’ve contracted it toxoplasmosis before becoming pregnant are immune, and will pass on that immunity. The danger is contracting it for the first time whilst pregnant and passing on congenital toxoplasmosis, which can cause miscarriage or stillbirth, or birth defects that may not develop until adulthood, including seizures, jaundice, liver enlargement, hearing or vision loss, low IQ, neurological disorders and mental disability.

Doctors still don’t understand how toxoplasmosis works, and can’t treat it, though new anti-malaria, anti-schizophrenia and nanoparticle-borne Estersantibody drugs are being explored.

Healthy adults humans are usually asymptomatic (though some get flu-like symptoms) and are considered dead-end accidental hosts, because toxoplasma gondii can only reproduce in cats – and wants to get back in cats. Some people think that toxoplasmosis can even change your behaviour, driving you to like cats, hang out with cats and, if you’re a rat, end up eaten by cats so the parasite can get back in cats.

However, you can’t toxoplasmosis directly from cats: you have to handle cat poo (where the eggs are excreted) from cats that have contracted the parasite for the first time (or lambs!): after that, like humans, they become immune. Another risk factor is handling soil, possibly because cats toilet outdoors. This is a bigger risk but can be mitigated by wearing gloves and hand-washing.

This is why some foods, such as “unwashed greens” are best avoided during pregnancy – they might be soil contaminated and the soil might contain toxoplasma gondii – washed greens are safe to eat.

Meat is the primary source of toxoplasmosis (30-63% of infections in Europe[53]), and is dangerous when undercooked (especially pork, lamb, and venison), cured (like salami), raw (such as oysters, clams, or mussels), or unpasteurised (dairy products).

However, risks vary with cultural eating habits, livestock health and local soil. Social trends also play a role, such as the fashions to eat raw food diets, including uncooked vegetables and meats. Free-range and organic meats are more likely to carry the parasite, simply because the animals spend more time outdoors on untreated land.

One study showed that 14 to 49% of infections still had an unidentified cause, primarily because of the difficulties involved in monitoring, detecting toxoplasma gondii in food, and in confirming sources[54] [55]. Scientists think there may be other unidentified sources in food and the environment[56].

Learn more about Toxoplasmosis (Things We Don’t Know about Pregnancy Series #6).

Things to avoid and environmental exposures

There are lots of things pregnant women are advised to avoid, including mobile phones, fire retardants, non-stick coatings, and endocrine disrupting chemicals such as bisphenol A and phthalates, found in many plastics and personal care products.

Whilst eating fresh rather than processed foods, minimising painting and use of cosmetics (or fancy pregnancy oils, creams and other unnecessary personal care products) are sensible moves, the exposure levels to these things are so low that they’re pretty much negligible anyway. However, these things do create confounding factors that make assessing the impact of particular foods, drinks or chemicals difficult if not impossible to quantify.

Many women turn to herbal teas as an alternative to caffeinated beverages, but be careful to do your research if you choose this path: not all herbal teas are safe for pregnant women. Herbal remedies tend to be unregulated, and natural concentrations of components can vary wildly, making amounts on packets rough guidelines at best. One recommended, safe tea is peppermint tea (which can even ease nausea, whilst chamomile is not a good idea (it can trigger uterine contractions). Nettle tea, meanwhile, is sometimes recommended, and sometimes recommended against.

Scientists aren’t sure whether nettle tea is safe during pregnancy, although this controversy may hinge on which parts of the nettle are used: bark, flowers, roots, berries, seeds and leaves are all common components. The root is generally not recommended and the leaf is recommended. The NHS recommend no more than 4 cups of herbal tea a day.

Nettles are high in vitamins A, C, K, magnesium, calcium, and iron, and often recommended by midwives for pregnant women as they can aid digestive issues and help with anaemia, joint and muscle pain, and the production of breast milk.

Some claim nettle tea, like chamomile, can lead to contractions and early labour.

More research is needed into its effects.

Alcohol

Medical advice is that no alcohol is safe during pregnancy, but what do the studies show?

Small amount of alcohol are probably fine. There is no proven harm to your unborn baby if you consume 1-2 alcoholic drinks a week in the first trimester, up to 1 drink a day in the second and third trimester, and consume them slowly, with food[29].

If a lot of alcohol is consumed around conception or shortly after, the probability of early spontaneous abortion is higher[59][60][61]. However, many women sadly terminate a pregnancy because they believe they have harmed the baby through drinking irresponsibly before they found out. This is entirely due to bad advice and lack of information allowed to women, because if conception is successful and miscarriage doesn’t take place, drinking this early (before the development of the nervous system) can’t cause foetal alcohol syndrome – it’s too early – the risk for that peaks at 6-9 weeks of pregnancy.

We still don’t know a lot about how alcohol or its harmful effects, research suggests it has multiple effects on the developing foetus, including[62][63]

Vitamins and supplements

2

2

Vitamin B12

Can you have a healthy pregnancy and be vegan, or even just vegetarian? Vegan and vegetarian cultures all over the world have survived healthily for thousands of years[65], so yes, it’s possible. But do you need to supplement?Most B vitamins are widely available in grains, but vitamin B12 (cobalamin) is a special case. This vital nutrient supports the functioning of the nervous system and blood formation, so is particularly important for pregnant women. However, it’s only found in trace amounts outside meat and dairy products, except in fortified foods like cereals, soya milks and yeast extract. Researchers are unsure whether vegan sources of B12 are adequate. This is because measuring the quantity of B12 in foods is very difficult: there are several molecules similar to B12 (known as “analogues”) that disrupt the body’s use of B12. This means that a food measured to contain B12 may actually not contain B12 at all, just its analogues. It’s also possible that both are present, in which case if the analogues are in similar quantities to the B12, the B12 may not be accessible. Food can only be declared a reliable source of B12 if there is evidence that it corrects or prevents deficiency.

Scientists are also unable to tell how long B12 stores in the body will last – they can diagnose deficiency, but not predict it.

If you get it naturally on a vegan diet, you may get it mostly from soil – yes, that’s right, from dirty vegetables. Whilst the liver can store B12 for up to 3 years, you can’t guarantee dirty vegetables will supply enough, and in any case should be avoided unwashed foods because of toxoplasmosis.

If you’re vegan, and if you’re pregnant, supplement for vitamin B12.

Omega acids

Only one type of omega 3 fatty acid – vital nutrients essential for brain development, blood and heart regulation – are found in vegetables: ALA or alpha-linolenic acid. The body can convert ALA into these other types, but it’s not very efficient. It’s not clear whether vegetarians and vegans need to supplement or not, though some recommend it.Fish, however, especially large fish such as tuna, can be a source of heavy metals such as mercury, which can damage the brain and nervous system. So how much fish should we eat? Does the risk of environmental contaminants outweigh the risk of being deficient in essential fatty acids at a time when you need them more than ever? A pregnant woman is, after all, growing at least one whole new brain from scratch, and she needs essential fatty acids to do that. This dilemma really needs addressing, because at the moment mothers are being pulled in two different directions.

Learn more about What must women avoid during pregnancy?.

Vitamin D

Vitamin D helps the body absorb calcium, and is thus important when you’re building baby bones. It’s found in fish, eggs, dairy, fortified breakfast cereals, beans, and green leafy vegetables, and is made by the body when exposed to sunlight (which does not mean there is no such thing as too much sunlight). This means that no matter what your diet, you can be deficient in vitamin D during the winter when it’s dark most of the time we’re outside and may need to supplement if you’re expecting a winter baby.

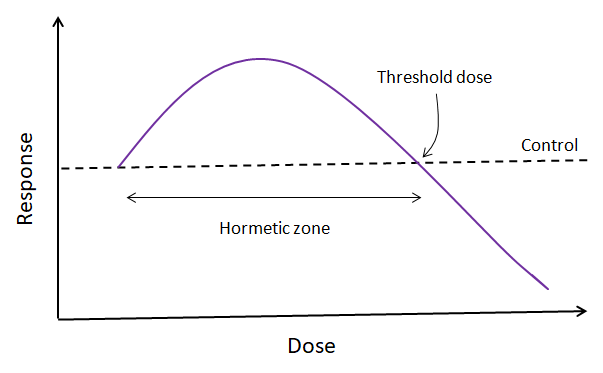

Vitamin A

Vitamin A is essential for growth and development, and healthy eyesight and immune system. As such, you’d think it was important for pregnant women to get lots of it, but in fact pregnancy vitamins are low on vitamin A and healthcare professionals warn against taking too much. This is because the liver stores it, and can accumulate dangerous levels, whereupon it starts to act as a toxin and cause birth defects in babies. Liver is also not recommended in the diet of pregnant women for the same reason. Normally, vitamin A levels in the livers of herbivores are safe, but during pregnancy you should watch out (carnivores, on the other hand, accumulate dangerous vitamin A levels, especially as they age, which is how Antarctic explorers poisoned themselves by eating dog liver during desperate time).

Folic acid

Folic acid helps us build proteins for growth, including the metalloprotein haemoglobin, and metabolise DNA. For pregnancy, we need 10 to 20 times as much as normal[66] to build neural networks, but this needs to be in your system before you conceive. This means that folic acid is an essential nutrient to get before having a baby and during the first trimester, coming mainly from green leafy vegetables, pulses and avocados, but also fortified in breakfast cereals and in pregnancy-specific vitamins.However, importantly, recent research has suggested that getting too much folic acid later in pregnancy can mask vitamin B12 deficiency[67] and may increase the risk of autism[68]. Current research is inconclusive and so ongoing. Luckily, it seems unlikely that it would be possible to get too much folic acid from foods naturally rich in it, and it takes supplementation or foods that are enriched to get too much.

Learn more about Vitamins and Supplements (Things We Don’t Know about Pregnancy Series #13).

Other diseases

Listeria is another key disease that can affect pregnant women. Whether or not she’s gone off them, there are lots of foods women are asked to avoid during pregnancy. This is because she is immunosuppressed, making her more vulnerable to food poisoning, like listeria. The immune cells that attack and destroy listeria have been seen to infiltrate the placenta, where they make a chemoattractant protein, CXCL9 that draws killer T cell antibodies through that harm the foetus. Scientists think that similar maternal infections could be behind many miscarriages, stillbirths and premature births.

For more about things best avoided during pregnancy, see our blog post on the subject.

In fact, autoimmune disorders may be triggered by harmful bacteria, viruses, or certain drugs, which mess up the body’s ability to differentiate between normal, healthy tissue and harmful substances. It could also have a genetic factor.

If your red blood cells are coated in an antigen known as rhesus D, you are rhesus positive. If they’re not, you’re rhesus negative. Rhesus state is inherited from the mother or a father, so a rhesus negative mother could carry a rhesus positive foetus if the father is also rhesus positive. In the UK, 85% of people are rhesus positive.

A pregnant rhesus negativewoman can come into contact with rhesus positive blood either when the placenta peels away during childbirth, or earlier if maternal and foetal bloods mix, such as after a fall or during a prenatal test. This sensitises the mother to rhesus positive blood, amplifying her immune response to it next time – usually during a second pregnancy. If the mother’s immune system attacks a foetus, this can lead to jaundice, heart failure, or enlarged organs. The mother herself won’t feel symptoms though – only the foetus suffers.

Rhesus disease is normally treated blood transfusion or early delivery.

Anti-phospholipid syndrome (APS) is an autoimmune disease that pregnant women can get, where anti-phospholipid antibodies are produced by the immune system. These attack the pre-embryo or trophoblast (outer cells from the blastocyst that give nutrients to the embryo and eventually become placenta), preventing it from staying implanted, and alter blood flow to the uterus. No one is sure why this comes about.

Mental healthBirth trauma

PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) is still a condition associated with soldiers. Men. But every year, estimates suggest 4% of births cause births cause maternal PTSD[69]. We call this birth trauma.

Birth trauma is triggered by intense physical ordeals, such as very slow/fast labour, over- or under-medication or gruelling interventions, and psychological ordeals, such as feeling lost control or dignity, not being heard, having medical things done to them they didn’t consent to or didn’t have explained to them, or not having information about the health of their baby when in a vulnerable position.

Symptoms include flashbacks, high anxiety, low mood and avoidant behaviours. It can affect sex lives, further childbearing, attendance at smear tests, bonding with their baby, and breastfeeding.

Birth trauma is under-reported, and many who report it won’t be treated or will be misdiagnosed with and treated for postnatal depression. The primary treatment is talking therapy, which is still being explored.

Researchers have suggested taking a preventative approach: screening women to identify who is most at risk of birth trauma. Initial findings suggest there could be structural indicators in the brain. The amygdala may be 6% larger in soldiers with PTSD than those without, although it’s unclear whether this is caused by PTSD or makes you susceptible to it, and whether this is also true for birth trauma. Some researchers are looking into whether existing PTSD theories are applicable to birth trauma or not, and whether research into childbirth could help us understand more about PTSD.

Other research is exploring the validity of birth memories. Hormones released after birth may help a woman gradually forget the pain of labour[70], although the literature suggests memories are still extensive, and having a negative experience of childbirth may prolong memories[71]. Others are looking into the unconscious brain or “the shadow” are affected by birth traumas.

It’s now thought that it may affect fathers who were present at the birth as well as mothers.

Postnatal depression

Postnatal depression is thought to occur in ~1 in 10 mothers, making it a common form of mental illness. The onset and peak of the illness may be weeks or even months after the birth of a baby, and the condition lasts for weeks, months, or longer. The condition is characterised by persistent negative feelings – towards yourself, your baby, and things you previously had an interest in. Most parents find their inability to bond to their baby most upsetting, and many feel guilty, hopeless, and even suicidal. Physical symptoms include disturbed sleep, tiredness, increased or decreased appetite, and difficulty decision-making.

We don’t know what causes it. Although it’s associated with hormonal changes, such as a drop in one hormone called allopregnanolone, these alone can’t explain everything. In the past, people believed that pregnancy hormones were protective against depression, and it was simply something new mothers couldn’t get – leading to many undiagnosed sufferers[72]. Scientists now think that a range of physical, emotional, genetic, and social factors contribute[73]. Risk factors include previous mental illness, physical or psychological trauma or abuse, stress, complications during childbirth, and use of drugs, cigarettes or other medications. Formula-feedings, low self-esteem, sleep deprivation and painful pre-menstrual symptoms may also cause or worsen the condition[74][75][76]. In one project, findings showed that the most important factor was how attached a mother was to her baby before it was born.

When the woman is depressed before the baby is born, this can correlate with low birth weight, poor growth, reduced activity, infections, difficulties breastfeeding, and even spontaneous abortion[77].

Men remain chronically underdiagnosed. They even experience hormone changes (such as drops in testosterone) when they become fathers. A 2016 literature study concluded that postnatal depression occurs in around 8% of men – almost as much as women[78]. However, screening tools for detecting it (the “Edinburgh scale”) are aimed at women, and may be less reliable in men[79][80].

There is no conclusive medication used to treat postnatal depression. Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are safe for pregnancy and breastfeeding, and seem to be effective after 2-3 weeks, but there is some suggestion that stopping the medication can lead to drug withdrawal symptoms such as jitters and seizures in the babies. Sometimes, sodium valproate is used to treat depression before pregnancy, but this medication can cause severe neurological damage in foetuses, and isn’t prescribed for women who develop depression during pregnancy or after.

Hormone therapies are being explored, and oestradiol patches might be effective. However, increased oestrogen can increase the risk of blot clots in new mothers, and the effect on breastfeeding is yet to be studied[81]. The newest drug is brexanolone, a synthetic version of the allopregnanolone hormone. Trials suggest it’s effective, but it’s injected, and, when administered, can lead to unconsciousness.

Drug alternatives includes psychological treatments such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), guided self-help, interpersonal therapy, problem-solving therapy and psychodynamic psychotherapy. These talking therapies have been shown to be effective in mental health treatments, but vary between individuals.

Others have tried acupuncture, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), or transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS). Evidence is inconclusive[82]. Lifestyle changes include bright light exposure, taking omega-3 fatty acid or vitamin D supplements, avoiding caffeine, and reducing stress[83] [84].

Others have pointed out that an effective screening programme – which would cost £20 million a year in the UK – would massively reduce the £8 billion a year maternal mental health bill.

One antidepressant is St John's wort (hypericum perforatum), a natural herb indigenous to the UK that can be used as a “dietary supplement” or over-the-counter medical treatment for mild depression and anxiety. It’s thought to work like a standard antidepressant, inhibiting serotonin reuptake. But there's still a lot we don't know about St John's wort. The chemical content can vary widely according to the size and health of the plant, the harvesting and drying processes, packaging and storage. It is a long-acting agent, with a half-life of 26.5 hours in the human body.

Not enough research has been done on the use of St John's wort to know whether it effects pregnant women or their babies. However, it has been found to increase uterine muscle tone in laboratory animals, and could potentially cause uterine contractions. One small study found higher rates of miscarriage in pregnancies where the mothers were taking St John's wort compared to another antidepressant or no antidepressant, but the rates between the three groups were not significantly different. There are no studies looking at withdrawal symptoms or effects on the baby’s behaviour or development.

Perinatal (or antenatal) depression

Depression that arises during pregnancy is known as perinatal (or antenatal) depression. Scientists think it affects 7% to 20% of women, but estimates vary around the world[85].

Rates of miscarriage (“spontaneous abortion”) are higher in women with perinatal depression. Scientists think this is linked to the condition rather than medication, as initial studies suggest rates are higher for women not undergoing treatment[86].

The Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children looked at 3,176 father and child pairs, where they found not only did 1 in 20 fathers developed postnatal depression, but this correlated with a small but significant increased risk of daughters (but not sons!) developing depression at age 18[88]. Scientists are unsure why the effect is only seen in girls.

Postpartum bipolar disorder

Postpartum bipolar disorder, the least well-known postpartum mental health disorder, is characterised by mood episodes of mania, hypomania or depression that interfere with everyday life and performing ordinary tasks. We don’t know the cause.

Postnatal (puerperal) psychosis

Postnatal (puerperal) psychosis is an uncommon but severe condition, which can include low mood – or manic mood – delusions, hallucinations, and out-of-character behaviour. No one’s sure what causes it, but trauma or a history of other mental illnesses are risk indicators.

Birth trauma, a type of PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) is mostly triggered by loss of control during childbirth, including not being heard, having medical things done without consent, or not knowing about the health of the baby.

The endometrium

Scientists know very little about the endometrium – the uterus lining. The wall of the uterus changes during the menstrual cycle and accepts the implantation of a fertilised egg during pregnancy[89]. As such, it is known that the endometrium responds to female sex hormones, but not which or how. It also produces its own chemicals.

IVF and infertility

Now, scientists think that IVF failure may be just due to timing. IVF works by suppressing the natural menstrual cycle, stimulating and gathering eggs, and then reintroducing fertilised eggs. If they are introduced too early or too late, however, the womb may not be ready to receive them, and they will be lost. For most women, this timing is guessed, but a pilot study that individualises treatment by studying women’s uterine cycles has shown a 33% success rate.

Immunological treatment, however, remains controversial. It’s hard to entangle immunological factors in success stories from other factors such as individualised support, changes in diet, and medical attention.

Some clinicians think high levels of natural killer cells from the uterus, might be associated with miscarriage. However, they may have a different role there to in the blood, remodelling blood vessels through the placenta; in fact, some research suggests low numbers of natural killer cells in the uterus may obstruct pregnancy and that they perform a benign role, preventing other immune cells from attacking the foetus[90][91]. There’s also no agreed way to get natural killer cell counts. Blood levels and uterine levels are not necessarily linked, and levels in the uterus vary with the menstrual cycle.

Statistical analyses of 21 antibodies have found no differences in implantation rates, pregnancy rates, or pregnancy outcomes for higher or lower concentrations. Some treatments have been outright refuted, such as leukocyte immunisation therapy, which may be dangerous[92][93].

Alloimmune disease might also affect fertility. Alloimmune disease happens when the female body launches an immunological attack on male tissues – basically killing off his sperm.

Semen and pre-eclampsia

However, in contrast to alloimmune responses against a partner’s sperm, exposure to sperm may sometimes prevent pre-eclampsia, a life-threatening pregnancy complication that sometimes arises in the second half of pregnancy[94]. This may be due to immune modulating factors in the seminal fluid.

Learn more about Reproductive Immunology (Things We Don’t Know about Pregnancy Series #7).

Nesting

Is nesting, cleaning, organising, decorating and stockpiling in preparation for a baby biologically or socially driven?

Animals nest from birds to fish, rodents, cats, dogs, pigs, and 80% of pregnant women. Pregnant dogs will steal blankets, cats will climb into haylofts, rabbits pluck out their own fur to line the burrow, sows leave the herd to travel up to 6.5km[95], and broody birds will insist on constant nest sitting. Marsupials don’t nest. They carry their young with them in a pouch, and scientists think this might be why.

When a pregnant female animal starts to nest, her oestradiol, prolactin and progesterone levels soar. When she stops, her oxytocin is high – the hormone responsible for contractions in labour. Shortly after the birth, progesterone levels drop, oestradiol stays steady, and prolactin keeps going up. The exact timings vary from species to species[96].

But not all nesters are pregnant females. Male and non-pregnant female animals sometimes nest. Scientists think this behaviour is performed to regulate temperature or endear themselves to a potential mate.

Up to 90% of men in a relationship with a pregnant woman show some kind of symptom (weight gain, morning sickness, mood swings, fatigue, disturbed sleep, labour pains(!)…) – called sympathetic pregnancy, or sometimes couvade syndrome. Some doctors think this is psychosomatic, whilst others think there may be stress hormones behind it[97].

Learn more about Nesting (Things We Don’t Know about Pregnancy Series #5).

Baby brain

The literature disagrees when it comes to the phenomenon known as “baby brain”. Is it real, or just a figment of women’s imaginations?

Most studies are very small, and study different areas of memory to each other (as well as attention span and executive function) on women at different stages of pregnancy or early motherhood[98][99][100][101]. Often, measured declines that are statistically significant still fit within the ordinary ranges of working adult memory. Multiple studies, however, have shown that having a baby and being a parent changes your brain, especially in later stages of pregnancy and parenthood, when your brain is the most plastic it ever is in adulthood[102][103][104]. And some suggests it improves memory and brain function[105][106]. This may be because, as some have suggested, baby brain is an important adaptive mechanism, promoting some neurological abilities, such as emotional bonding, at the expense of others.

The most unexplored areas of the baby brain phenomenon are what happens after the immediate postpartum period, and the underlying mechanism behind it. Interestingly, whilst losses in grey matter have been reported in the hippocampus area of mothers’ brains, two years later, brains look the same again as they did before, suggesting that changes may not be permanent[107]!

What are the mechanisms behind baby brain?

Various studies propose different ideas. Some who have suggested that the effects are not “real” think they could be explained by other consequences of pregnancy and early parenthood, including tiredness and disturbed sleep, stress, morning sickness, and mood changes.

Others think hormones are responsible, which rise to 15-40 times their usual levels during pregnancy and effect neurons in the brain! In particular, oxytocin, which has shown links to behaviour, learning and memory in animals.

Learn more about Baby Brain (Things We Don’t Know about Pregnancy Series #14).

![Lateral View of the Brain By BruceBlaus [CC BY 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons](/img/sci/Blausen_0101_Brain_LateralView_512.png)

Biological sex

Identifying the biological sex of an unborn baby can be difficult, even with ultrasound: sometimes the baby just doesn’t cooperate, and accuracy only rises to 100% after 14 weeks gestation, with a success rate starting at 75% during the 12-week scan [108]. For some, knowing the sex of their baby early is especially important if they carry a serious genetic disease that affects one sex. For these women, invasive techniques may be used to collect foetal DNA, which can increase risk of miscarriage, so increasing ultrasound accuracy could save lives. Possible develops include cross-section imaging (allowing us to see “through” legs that are in the way).

To find out more about determining the sex of a baby, read our dedicated article on the subject.

Learn more about Determining the Sex of a Baby (Things We Don’t Know about Pregnancy Series #12).

What causes SIDS, and why mention it in pregnancy?

Sudden Unexplained Infant Deaths (SUIDs) of infants under a year old occur unpredictably and don’t have an obvious cause. Of around 200 such deaths in the UK every year, around 80% are classified as SIDS – Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (also know as cot death). These are the deaths that can’t later be explained by suffocation, infections, or genetic disorders, even after autopsy.

But what does this have to do with pregnancy?

Many risk factors are linked to their mother’s health and what happens before and when they’re born.

Maternal health during pregnancy is a key indicator for SIDS risk. Mums younger than 20, who smoke or take drugs, or get poor prenatal care are more likely to have babies that suffer from SIDS[109]. They’re also more likely to have babies born prematurely (increasing their risk x 4) or underweight (increasing their risk by x 5.7 for 1000–1499 g babies versus 3500–3999 g babies)[110]. An elevated risk is even seen in full term babies born before 39 weeks.

Some risk factors are a bit connected to pregnancy and a bit not, for example, minor illnesses (such as anaemia[111]); these can be out of your control, but chances may be reduced by staying healthy during pregnancy (in the case of anaemia, eating tons of iron-rich food) and getting all the requisite vaccinations.

Scientists think SIDS may be due to a combination of developmental challenges and environmental stressors. This means that when the babies get stressed, their bodies do the wrong thing to respond. If they’re delayed in developing good breathing, immune, cardiovascular, or temperature regulation. One example is “rebreathing”, where they have restricted air access (e.g. because they’re on their tummy) and so start breathing their own exhaled air again and again, until oxygen levels are too low and carbon dioxide too high. The brain should wake a sleeping baby and make them cry if this happens, but if it hasn’t developed properly yet, they won’t.

There could also be a seasonal component, since more SIDS deaths occur in winter. However, this could instead be because parents use more bedding or babies are more likely to get sick.

And there are genetic factors. For example, boys are more likely to suffer from SIDS; one study cited a 50% male excess in SIDS per 1000 live births of each sex[112].

There may be a racial component too (although it’s not clear from the literature whether this has been disentangled from socioeconomic components).

You can reduce your baby’s risk of SIDS by sleeping them on their back, in their own space, with their feet at the end of the crib and the blanket below their shoulders, not smoking around them, and getting them vaccinated (which approximately halves risk)[113][114][115][116][117][118]. Breastfeeding also seems to reduce the risk of SIDS[119]. This is probably because it equips the newborn with more antibodies bequeathed by mum sooner, boosting their immune system.

Evidence even suggests pacifiers/dummies may help reduce the chance of SIDS (by 90%!) and eliminate the risk posed by soft bedding. Whilst scientists don’t know why this is, it’s probably because the bulky handle prevents the baby from burying their face in their bedding)[113].

To read more about SIDS, check back soon for a dedicated article on the subject!

This article was written by the Things We Don’t Know editorial team, with contributions from Freya Leask, Ginny Smith, Cait Percy, Johanna Blee, Kat Day, and Rowena Fletcher-Wood.

This article was first published on 2019-10-19 and was last updated on 2020-02-28.

References

why don’t all references have links?

[1] Czaja, John A. Food rejection by female rhesus monkeys during the menstrual cycle and early pregnancy.Physiology & behavior 14.5 (1975): 579-587.

[2] Flaxman, Samuel M., and Paul W. Sherman. Morning sickness: a mechanism for protecting mother and embryo. The Quarterly review of biology 75.2 (2000): 113-148.

[3] Flaxman, Samuel M., and Paul W. Sherman. Morning sickness: adaptive cause or nonadaptive consequence of embryo viability? The American Naturalist 172.1 (2008): 54-62.

[4] Hakim, Rosemarie B., Ronald H. Gray, and Howard Zacur. Alcohol and caffeine consumption and decreased fertility. Fertility and sterility 70.4 (1998): 632-637.

[5] Schuster, K., et al. Morning sickness and vitamin B6 status of pregnant women. Human nutrition. Clinical nutrition 39.1 (1985): 75-79.

[6] Chittumma, Porndee, Kasem Kaewkiattikun, and Bussaba Wiriyasiriwach. Comparison of the effectiveness of ginger and vitamin B6 for treatment of nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy: a randomized double-blind controlled trial. Journal-medical association of Thailand 90.1 (2007): 15.

[7] Crystal, Susan R., and Ilene L. Bernstein. Infant salt preference and mother's morning sickness. Appetite 30.3 (1998): 297-307.

[8] Crystal, Susan R., and Ilene L. Bernstein. Morning sickness: impact on offspring salt preference. Appetite 25.3 (1995): 231-240.

[9] Vargesson, N., 2015. Thalidomide‐induced teratogenesis: History and mechanisms. Birth Defects Research Part C: Embryo Today: Reviews, 105(2), pp.140-156.

[10] Mori, T., Ito, T., Liu, S., Ando, H., Sakamoto, S., Yamaguchi, Y., Tokunaga, E., Shibata, N., Handa, H. and Hakoshima, T., 2018. Structural basis of thalidomide enantiomer binding to cereblon. Scientific reports, 8(1), p.1294.

[11] Borgna-Pignatti, Caterina, and Sara Zanella. Pica as a manifestation of iron deficiency. Expert review of hematology 9.11 (2016): 1075-1080.

[12] Ventura, A. K., & Worobey, J. (2013). Early influences on the development of food preferences. Current biology, 23(9), R401-R408. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.02.037.

[13] Şükür, Yavuz Emre, et al. The effects of subchorionic hematoma on pregnancy outcome in patients with threatened abortion.Journal of the Turkish German Gynecological Association 15.4 (2014): 239.

[14] Brezinka, Christoph, et al. Denial of pregnancy: obstetrical aspects. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology 15.1 (1994): 1-8. doi: 10.3109/01674829409025623.

[15] Del Giudice, Marco. The evolutionary biology of cryptic pregnancy: A re-appraisal of the denied pregnancy phenomenon. Medical hypotheses 68.2 (2007): 250-258. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2006.05.066.

[16] Yadav, Tarun, Yatan Pal Singh Balhara, and Dinesh Kumar Kataria. Pseudocyesis versus delusion of pregnancy: differential diagnoses to be kept in mind. Indian journal of psychological medicine 34.1 (2012): 82. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.96167.

[17] Adityanjee, A. M. Delusion of pregnancy in males: a case report and literature review. Psychopathology 28.6 (1995): 307-311. doi: 10.1159/000284942.

[18] Chatterjee, Seshadri Sekhar, et al. Delusion of pregnancy and other pregnancy-mimicking conditions: Dissecting through differential diagnosis. Medical Journal of Dr. DY Patil University 7.3 (2014): 369. doi: 10.4103/0975-2870.128986.

[19] Manjunatha, Narayana, and Sahoo Saddichha. Delusion of pregnancy associated with antipsychotic induced metabolic syndrome. The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry 10.4-2 (2009): 669-670. doi: 10.1080/15622970802505800.

[20] Chapter 4 - Abnormal development of the conceptus and its consequences, pp. 119-143. In: Noakes, D.E, Parkinson, T.J., England, C.W., & Arthur, G.H. (2001) Arthur's Veterinary Reproduction and Obstetrics 8th Edition. Elsevier Ltd. ISBN: 978-0-7020-2556-3. doi: 10.1016/B978-070202556-3.50008-6.

[21] Roellig, K., Menzies, B. R., Hildebrandt, T. B., & Goeritz, F. (2011). The concept of superfetation: a critical review on a ‘myth’ in mammalian reproduction. Biological Reviews, 86(1), 77-95. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2010.00135.x.

[22] Roellig, K. et al. Superconception in mammalian pregnancy can be detected and increases reproductive output per breeding season. Nat. Commun. 1:78 doi: 10.1038/ncomms1079 (2010).

[23] Harrison, A., Valenzuela, A., Gardner, J., Sargent, M. & Chessex, P. Superfetation as a cause of growth discordance in a multiple pregnancy. The Journal of Pediatrics 147:2, 254-255 (2005). doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.04.038.

[24] Hall, W.D., 1999. Representation of blacks, women, and the very elderly (aged> or= 80) in 28 major randomized clinical trials. Ethnicity & disease, 9(3), pp.333-340.

[25] Rochon, P.A., Berger, P.B. and Gordon, M., 1998. The evolution of clinical trials: inclusion and representation. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 159(11), p.1373.

[26] Murthy, V.H., Krumholz, H.M. and Gross, C.P., 2004. Participation in cancer clinical trials: race , sex , and age-based disparities. Jama, 291(22), pp.2720-2726.

[27] Schwab et al. Nonlinear analysis and modeling of cortical activation and deactivation patterns in the immature fetal electrocorticogram. Chaos An Interdisciplinary Journal of Nonlinear Science, 2009; 19 (1): 015111 DOI: 10.1063/1.3100546.

[28] Abrams, Barbara, Sarah L. Altman, and Kate E. Pickett. Pregnancy weight gain: still controversial. The American journal of clinical nutrition 71.5 (2000): 1233S-1241S.

[29] Emily Ostler, Expecting Better: Why the Conventional Pregnancy Wisdom is Wrong - and What You Really Need to Know (2013) Penguin Press.

[30] Fraser, Abigail, et al. Association of maternal weight gain in pregnancy with offspring obesity and metabolic and vascular traits in childhood. Circulation 121.23 (2010): 2557.

[31] Reynolds, R. M., et al. Maternal BMI, parity, and pregnancy weight gain: influences on offspring adiposity in young adulthood. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 95.12 (2010): 5365-5369.

[32] King V, Dakin RS, Liu L, et al. Maternal obesity has little effect on the immediate offspring but impacts on the next generation. Endocrinology. 2013.

[33] Dominguez-Bello, M. G. et al. Proc Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 11971–11975 (2010).

[34] Nature 572, 423-424 doi: 10.1038/d41586-019-02348-3.

[35] Deneux-Tharaux, Catherine, et al. Postpartum maternal mortality and cesarean delivery. <Obstetrics & Gynecology 108.3 (2006): 541-548.

[36] Fitzpatrick, Kathryn E., et al. Planned mode of delivery after previous cesarean section and short-term maternal and perinatal outcomes: A population-based record linkage cohort study in Scotland. PLoS medicine 16.9 (2019).

[37] Zhang, Tianyang, et al. Association of cesarean delivery with risk of neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorders in the offspring: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA network open 2.8 (2019): e1910236-e1910236.

[38] Formby, David. Maternal recognition of infant's cry. Developmental medicine & child neurology 9.3 (1967): 293-298.

[39] Marlin, Bianca J., et al. Oxytocin enables maternal behaviour by balancing cortical inhibition. Nature 520.7548 (2015): 499.

[40] Swain, James E., et al. Maternal brain response to own baby‐cry is affected by cesarean section delivery. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry 49.10 (2008): 1042-1052.

[41] Gustafsson, Erik, et al. Fathers are just as good as mothers at recognizing the cries of their baby. Nature Communications 4 (2013): 1698.

[42] De Pisapia, Nicola, et al. Gender differences in directional brain responses to infant hunger cries. Neuroreport 24.3 (2013): 142.

[43] Van den Berg, Merel MJ, et al. Genetics of early miscarriage. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular Basis of Disease 1822.12 (2012): 1951-1959..

[44] Chan, William FN, et al. Male microchimerism in the human female brain. PLoS One 7.9 (2012): e45592.

[45] Gammill, Hilary S., et al. Effect of parity on fetal and maternal microchimerism: interaction of grafts within a host?.

[46] Ursini, Gianluca, et al. Convergence of placenta biology and genetic risk for schizophrenia. Nature medicine 24.6 (2018): 792.

[47] Begley, Cecily M.; Gyte, Gillian M. L.; Devane, Declan; McGuire, William; Weeks, Andrew (2015-03-02). Active versus expectant management for women in the third stage of labour. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD007412. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007412.pub4. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 4026059. PMID 25730178.

[48] Mercer JS, Vohr BR, Erickson-Owens DA, Padbury JF, Oh W (2010). Seven-month developmental outcomes of very low birth weight infants enrolled in a randomized controlled trial of delayed versus immediate cord clamping. Journal of Perinatology. 30 (1): 11–6. doi:10.1038/jp.2009.170. PMC 2799542. PMID 19847185.

[49] Perez-Muñoz, Maria Elisa; Arrieta, Marie-Claire; Ramer-Tait, Amanda E.; Walter, Jens (2017). A critical assessment of the sterile womb and in utero colonization hypotheses: implications for research on the pioneer infant microbiome. Microbiome. 5 (1): 48. doi:10.1186/s40168-017-0268-4. ISSN 2049-2618. PMC 5410102. PMID 28454555.

[50] Mor, Gil; Kwon, Ja-Young (2015). Trophoblast-microbiome interaction: a new paradigm on immune regulation. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 213 (4): S131–S137. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2015.06.039. ISSN 0002-9378. PMID 26428492.

[51] Prince, Amanda L.; Antony, Kathleen M.; Chu, Derrick M.; Aagaard, Kjersti M. (2014). The microbiome, parturition, and timing of birth: more questions than answers. Journal of ReproductiveImmunology. 104–105: 12–19. doi:10.1016/j.jri.2014.03.006. ISSN 0165-0378. PMC 4157949. PMID 24793619.

[52] Hornef, M; Penders, J (2017). Does a prenatal bacterial microbiota exist?. Mucosal Immunology. 10 (3): 598–601. doi:10.1038/mi.2016.141. PMID 28120852.

[53] Cook AJ, Gilbert RE, Buffolano W, Zufferey J, Petersen E, Jenum PA, Foulon W, Semprini AE, Dunn DT. Sources of toxoplasma infection in pregnant women: European multicentre case-control study. European Research Network on Congenital Toxoplasmosis. BMJ. 2000 Jul 15; 321(7254):142-7.

[54] Robert-Gangneux F, Dardé ML. Clin Microbiol Rev. Epidemiology of and diagnostic strategies for toxoplasmosis. Clinical microbiology reviews 25.2 (2012): 264-296.

[55] Singh A.K., Verma A.K., Jaiswal A.K., Sudan V., Dhama K. Emerging food-borne parasitic zoonoses: A Bird’s eye view. Adv. Anim. Vet. Sci. 2014;2:24–32. doi: 10.14737/journal.aavs/2014/2.4s.24.32.

[56] Hussain, Malik, et al. Toxoplasma gondii in the Food Supply. Pathogens 6.2 (2017): 21.

[57] Standridge, John B., Robert G. Zylstra, and Stephen M. Adams. Alcohol consumption: an overview of benefits and risks. Southern Medical Journal 97.7 (2004): 664-673.