Microbiome

Article curated by Rowena Fletcher-Wood

You have an ecosystem living in your gut.

It feeds off you, even creates the gases you let rip when you pass wind, and, symbiotically, makes a quarter of your vital vitamins and extracts some of the nutrients you need from food.

The Ecosystem in Your Gut

It might even determine your tastes in food and whether you are fat or thin. Until recently, nobody knew very much about gut microbes or what they were doing in there – except creating gas – but now, dieticians think some of our basic ideas about food could be wrong – such as treating all calories as equal.

Learn more about how the microbiome influences food choice.

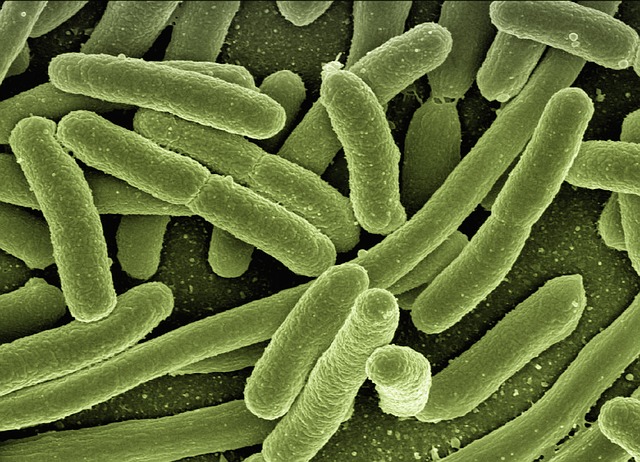

It might be our microbiome – consisting of the ecosystem of microbial life forms swarming about inside us – that determines how food affects our bodies. Microbes may have the power to switch on genes, or be selected by genes – not as shocking as it originally sounds when you realise that, because we evolved from them, we are 40% microbe[1]. But our microbial makeup really is unique. We only share 10-20% of our microbes with friends and family, whilst we share 99.5% of our DNA[2].

The microbiome is more similar in twins, but can still vary hugely between family members, especially those born by caesarean section[3]. This is because we are all born microbe-free, sterile, perfect if you like, except that we can’t digest anything[4][5]. Researchers think we get our first microbes from our mother by getting a mouthful of placenta during the birthing process. Babies born by caesarean section get their first microbes from random strangers, doctors, nurses, and friends who want to hold them. Although they will pick up some microbes from their parents through touching and breastfeeding, they may get some “wrong” microbes for their genetics. As a result, caesarean babies might be more likely to be fatter and more likely to get allergies (this theory is considered controversial though)[5].

2

2![Baby By Beth [CC BY 2.0], via Flickr](/img/sci/baby.jpg)

On the other hand, you can change your microbiome and make a better one just by going round touching people. Microbes can be transferred through bodily fluids, faeces, and even skin to skin contact. This means that every time you shake hands with somebody, you are literally offering them your microbes. However, it’s important to remember that changing your microbiome is a bit like using a fork to extract a piece of stuck toast from a toaster (never do this): sometimes it works, and sometimes it doesn’t.

Greater microbial diversity is represented in healthy individuals, whilst those suffering from conditions tend to show a barren microbiome that lacks in diversity.

Weight

Researchers are looking into less random ways to change your microbiome. One suggestion is hormone therapy, creating an environment that moderates your appetite and therefore encourages changes in eating patterns to eat less and to eat less snack food. This in turn should increase the diversity of your gut microbiome. At the moment, this research is still in its early stagers: researchers at Imperial College London are running clinical trials in bariatric patients. So far, results look positive, but the long-term effect of this hormone interference is not yet known. If proven safe, obese patients will have daily injections until they reach a healthy weight. What will happen after this point when the medication is withdrawn is not yet clear.

Pre-biotics – nutrients that feed our intrinsic gut bacteria – could also play an important role in weight regulation. When consumed, pre-biotics stimulate the release short chain fatty acids, which in turn cause the secretion of gut hormones that tell us to stop eating when we’re full. Although we don’t know why, evidence suggests pre-biotics make the metabolism more efficient. Amongst various possible mechanisms, one research group at Oxford University are exploring how gut bacteria could train the immune system, making us less reactive to inflammation by outcompeting harmful bacteria or producing anti-inflammatory molecules.

Psychologists are currently testing pre-biotics in animals on antipsychotics to find out how these two drugs interact. Antipsychotics cause weight gain in some patients, whilst pre-biotics can prevent weight again, so they could form a complementary medicine.

Mental Health

So does this mean that the microbiome can impact our mental health? It might. An individual collection of gut bacteria can influence the brain via inflammation, the immune system, and what you want to eat. In addition, microbes can produce chemicals, some of which may be toxic, or may mimic other biological molecules such as hormones and neurotransmitters. These chemicals will then alter our body chemistry and behaviours, how we metabolise chemicals in our bloodsteam, and therefore what reaches our brain. Some gut bacteria even directly stimulate nerves sending signals to the brain via the vagus nerve. Researchers think that, collectively, these mechanisms could affect sleep, stress, memory and mood – but still don’t know precisely how.

Some research on pre-biotics suggests they may be able to sharpen the mind, and could even impact children’s progress in school. Although this seems wildly far-fetched, this discovery could open the door to chemical and biochemical intellectual engineering via dietary and microbiotic management.

Physical Health

The microbiome has been linked to other diseases too, such as food allergies, bowel diseases, and even autism. Some of this is discussed in our other article: The Beast with a Billion Backs. Crohn’s disease, for example, could well be caused by microbial dysbiosis – or it could cause it. Although the link is established, the presence or direction of a cause-effect relation is not. Understanding whether to treat physiological or environmental triggers could lead down entirely different avenues in medicine.

Medical professionals don’t know what causes chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyeliti, nor how it operates. But it may also be linked to the microbiome. Chronic fatigue syndrome is a medical condition where the mitochondria in human cells don’t produce energy efficiently, leaving the sufferer debilitated with exhaustion, often unable to walk or exert themselves physically or mentally. It effects over 125,000 people in the UK, and attracts significant stigma, with accusations that sufferers are simply “lazy”. In the past few years, researchers have uncovered evidence of an unusual immune response in sufferers triggering cytokine immune messenger molecules at unexpected times. Whilst evidence suggests the disease is not autoimmune, a link does exist between the immune system and metabolism. This has led researchers to explore how the microbiome might influence the immune system, and vice versa.

Enhance your inner microbes

For those desperate to increase their microbial diversity, you can touch people, eat a varied diet (hunter gatherers eat ~500 more plants and animals than us, and have 30% more microbes[6]), or, now on the market from 500 US centres... buy crapsules. These are small capsules of frozen poo from healthy donors, and they do increase your microbial diversity. The problem is, we don’t know if shoving that many alien microbes down yourself is really a good idea, and you can’t be sure what microbes will find a home in you, and which ones will get overwhelmed by enemy forces.

When some crapsule consumers found that after taking a course, they got a lot fatter, the samples were traced back to overweight donors[7]. So now it looks like obesity can be passed on like an infectious disease: via your microbes. This could contribute to the common phenomena of happy couples gaining weight together: after all, they are sharing their fatty microbes. On the other hand, sprinkling a skinny microbe on your cereal won’t necessarily make you Jennifer Anniston. And there is one: the hitherto relatively unknown christensenella microbe, common in the skinny and rare in the pudgy[8]. You can apparently even buy christensenella online now – but not with a guarantee on it.

Learn more about Metabolic impact of faecal microbiota transplants.

You can also make your microbiome barren – if, for any reason, you’d want to. This is easily achieved by eating a lot of junk food. One experiment performed on a destitute student profiled his microbiome, left him to eat McDonald’s for 10 days, then profiled it a second time. Shockingly, the student saw a 40% loss in microbial diversity – equivalent to the destruction of 1,400 species. You can also take lots of antibiotics. As the name might suggest, these drugs don’t bode well for bacterial life forms – any bacterial life forms, and swallowing a few doses means taking an axe to your microbial diversity. A lot of the antibiotics we consume are actually in animal products; this filters through to our food and we end up eating it without even knowing.

Learn more about Impact of antibiotics on our microbiome.

2

2

This does mean that vegetarians are likely to be more microbially diverse – assuming they are healthy. Vegetarians who eat nothing but cheese toasties do not have healthy microbiomes, whilst occasional meat eaters may be equally diverse, and are health-wise more similar to vegetarians than to processed-sausage-junkies.

What to Cut

One major dietary misconception is that the way to get thin is to cut stuff out. Whilst if you entirely cut out something important, you might starve yourself thin, you’d also deplete your microbial diversity, leading to illnesses. In fact, if you took all the diet advice in one, you’d end up just downing vitamin tablets with kale juice. This might not sound terrible for kale lovers like me, but taking regular multivitamins is actually linked to increased risk of heart disease or cancer. We don’t know why – it could be because of the fibre, or single stereoisomers of vitamins found in supplements – but swallowing a broccoli vitamin tablet just doesn’t do the same good stuff as eating broccoli[9]. It might even upset your microbiome.

2

2

Now the French eat a lot of cheese... but have less heart disease than the English. This goes against our expectations and begs the question of whether the French have better genes... or better cheese? It’s certainly true that unpasteurised cheeses, like soft bries and camemberts, contain more microbes; they are probiotic, a moist, nutrient-rich breeding ground for anything microscopic and wriggling. In fact, the guest list of microbial entities that might be found in your mouthful of roquefort include, fungi, bacteria, viruses, and, weirdly and wonderfully, cheese mites. And microbial diversity helps.

In one mega study, 7000 Spanish people at risk of heart disease were put onto two diets with the same amount of fruit and veg: one was a typically prescribed low fat diet of lean meat and low fat yoghurt, and one was Mediterranean style, with lots of seeds, nuts, olive oil, fishes, meats and yoghurt in it – all that good stuff they say not to have if you have a heart condition[10]. And the funny thing was that after 4.8 years they had to terminate the study because there were a third more deaths from the low fat diet than the Mediterranean one. Researchers speculate that this is because of pro- and pre-biotics: microbial wombs and microbial fertilisers[10]. There are plenty of these in oils and seeds, as well as in other forbidden foods like chocolate (dark), wine, green tea and coffee (which contain polyphenols), or vegetables, which contain a pre-biotic called inulin. Inulin-rich foods include Jerusalem artichokes, chicory, garlic, onion and leek. Yoghurt, of course, is a pro-biotic, and actually has been shown to be effective fighting against any disease – if you’re a rat[11]. In humans, it only appears to make a difference for those with depleted or delicate microbiomes: the very old, the very young, or the very sick. Otherwise, yoghurt does not appear to affect people much. The explanation for this is that we’re all too genetically and microbially different: yoghurt cannot supply everything else we need, and it’s harder to change a healthy gut than an unhealthy one.

Weirdly, yoghurt is one of those things people like to cut from their diet – because it’s fatty. Women especially avoid yoghurt or accept low fat versions, and yet studies suggest this might affect fertility[12]. In fact, some researchers speculate that women should avoid fats and eat lots of fibre and protein during their periods to ease menstrual pain, and eats lots of them outside this to increase their fertility and boost the oestrogen to feel normal and feminine. However, not all studies agree[12][13], and researchers do not yet know what this would do to the female body long term, and whether it would result in a more or less healthy lifestyle.

The fate of the microbiome after death is less understood than the microbiome whilst we’re alive. However, it’s clear that human gut microflora play an essential role in the natural decomposition process and has even been proposed as a forensic tool for estimating time since death, or postmortem interval. As cells start autolysis (self-digestion), breaking up cell membranes and releasing macromolecules, the microflora get feeding. Research has focussed on what happens next, how they target molecules and how this affects the state of the human body and the chemicals found in it. Early research has shown that, over time, the richness of human gut bacterial communities significantly increases and, at the same time, the diversity decreases.

So how can you diet to lose weight if you can’t cut anything out? The answer is to cut everything – a bit. If you want to diet, the best method is to fast, or simply eat less food, whilst continuing to eat broadly across the spectrum of foodstuffs. Contrary to some diet advice, there is no evidence that skipping meals will harm your health long term, and indeed tests in rodents have shown that the best way to live longest is calorie restriction: eating just enough to get by in life, and no more than that.

This article was written by the Things We Don’t Know editorial team, with contributions from Gavin Hub, Ed Trollope, Ginny Smith, and Rowena Fletcher-Wood.

This article was first published on 2016-10-19 and was last updated on 2019-06-27.

References

why don’t all references have links?

[1] Melinda Wenner (2007). Humans Carry More Bacterial Cells than Human Ones. Scientific American November 30, 2007. (web)

[2] Levy, S., et al., (2007) The Diploid Genome Sequence of an Individual Human PLoS Biology 5(10):e254- DOI: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050254

[3] Turnbaugh, Peter J., et al. "A core gut microbiome in obese and lean twins." Nature 457.7228 (2009): 480-484.

[4] Grölund, M. M., Lehtonen, O. P., Eerola, E., & Kero, P. (1999). Fecal microflora in healthy infants born by different methods of delivery: permanent changes in intestinal flora after cesarean delivery. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition, 28(1), 19-25.

[5] Björkstén, B. (2005). Genetic and environmental risk factors for the development of food allergy. Current opinion in allergy and clinical immunology, 5(3), 249-253.

[6] Stephanie L. Schnorr., (2015). Hunter–Gatherers Have Diverse Gut Microbes. Scientific American March 1, 2015. (web)

[7] Alang, N., and Kelly, C.R., (2015) Weight Gain After Fecal Microbiota Transplantation. Open Forum Infectious Diseases 2.1 DOI: 10.1093/ofid/ofv004

[8] Goodrich, J., et al., (2014) Human Genetics Shape the Gut Microbiome Cell 159(4):789-799 DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.053

[9] van Poppel, G., van den Berg, H., (1997) Vitamins and cancer Cancer Letters 114(1-2):195-202 DOI: 10.1016/S0304-3835(97)04662-4

[10] Estruch, R., et al., (2013) Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease with a Mediterranean Diet New England Journal of Medicine 368(14):1279-1290 DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200303

[11] Adolfsson, Oskar, Simin Nikbin Meydani, and Robert M. Russell. (2004) "Yogurt and gut function." The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 80.2 : 245-256.

[12] Chavarro, J., et al., (2007) A prospective study of dairy foods intake and anovulatory infertility Human Reproduction 22(5):1340-1347 DOI: 10.1093/humrep/dem019

[13] Nagata, C., et al., (2004) Associations of menstrual pain with intakes of soy, fat and dietary fiber in Japanese women European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 59(1):88-92 DOI: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602042

Blog posts about microbiome

Recent microbiome News

Get customised news updates on your homepage by subscribing to articles