Plastics

Article curated by Rowena Fletcher-Wood

One of the properties which makes plastics so useful is their durability: their resistance to going soggy, crumbling, rusting or breaking down under normal environmental conditions. But this is also what makes them so difficult to dispose of – why? What happens to plastics when they are disposed of into the environment, and how might it affect us?

Around 8% of the world’s annual oil consumption goes into making new plastics. This is mostly waste oil, and so plastic packaging can save energy, waste and emissions relative to alternative options such as paper[1]. But half of the plastic we use is thrown away after just one use, simply because it’s designed that way. Coloured, shaped and hardened plastics can’t be recycled or reused easily and often end up on the streets, washed into waterways or piled up in landfill. The waste in a landfill may not even decompose over time. Not even all food waste decomposes; in order to contain harmful waste, many landfill sites are isolated by lining the bases with clay and plastic and covering the top with soil, preventing air and light from entering. Under these conditions, decomposition is very, very slow.

Plastic which doesn’t go into landfill sites often ends up in the ocean, sometimes via dumping or travelling along other waterways. There are even vast wastelands of plastic waste that form in open areas of ocean where currents mix and meet. Even if we started cleaning up these plastic wastelands now, we would probably still be throwing more plastic into the ocean faster than we could fish it out[2]. However, despite this prominence of plastic waste, it is estimated that about 99% of the world's waste plastic cannot even be found…[3].

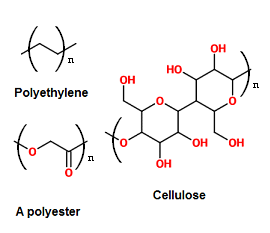

Plastics exist in nature too. Natural plastics include cellulose and rubber, which break down more easily than man-made plastics because natural enzymes in the bodies of animals and microorganisms in the environment have evolved to decompose them.

Man-made plastics are built of long polymers with lots of carbon-carbon bonds and a few different atoms. These extra atoms can affect how easily the plastic degrades; plastics with more reactive atoms in them like oxygen break down more easily. Plastics degrade via oxidation, hydrolysis and depolymerisation[2]. These may be catalysed by microorganisms or occur more slowly on exposure to light, water and oxygen.

Rigid plastics - thermosetting plastics - have extra links between the polymer chains, making them stronger and firmer, but harder to melt and break apart. These plastics are deliberately made like this for uses such as packing crates or sports equipment where they need to last. Other plastics may be engineered to biodegrade more readily – mimicking some natural polymers. These so-called “biopolymers” include “weak points” – chemical groups that make it easy for them to break apart. One example is an ester link: which importantly includes oxygen atoms interrupting the hard carbon chain. But biopolymers can break down too easily for many applications, and often additives to stabilise a plastic are introduced instead.

.jpg)

Large Plastic Items

It's possible that large pieces of “missing” plastic have actually sunk to the bottom of the ocean, where we can no longer see them. Whether they float or sink, all plastics in the ocean may be populated by biota: small plant and animal marine life. Biota alter the density of the plastics they inhabit, and may lead to repeated cycles of sinking and floating.

Alternatively, large pieces of plastic may have been broken down into smaller, dispersed fragments more rapidly than scientists estimated - which explains why they are so difficult to find. Although common microorganisms will not break down classic man-made plastics, plastics do undergo photodegradation under ultraviolet sunlight, eventually turning brittle and cracking. At temperatures higher than 50 °C some plastics will biodegrade in just one year[4]. But very little is known about how plastics break down in cool seawater, especially at depths where there's not much light.

Before they're broken down into smaller chunks, big pieces of plastic pose additional risks, especially if they are washed ashore. Here, animals may become entangled, and may be injured or killed[5]. The amount of plastic washed ashore on beaches is also a big clue as to the sheer size of this hidden iceberg of a plastic waste problem…

Small Plastic Items

Smaller plastic items like bottle lids and toys are more likely to be made of brittle thermosetting plastics that take longer to break down. These items are frequently consumed by birds and marine mammals, which cannot be digested and so accumulate inside them. It is unclear whether this affects their behaviour, lifetime or ability to reproduce, but not knowing the effects of plastic consumption is in itself worrying. Plastics that contain stabilising additives are more likely to be toxic and harmful, but as yet there is no measure of their effects.

Some researchers have studied the distribution of plastic items in the stomachs of organisms, but because of the migratory nature of birds and the currents in the oceans, it's impossible to pin down where it all came from. Plastic items are found in the stomachs of animals around the globe[6].

Learn more about Plastic pollution.

Microplastics

Microplastics may be the result of big pieces of plastic that have been broken down, released from clothes fibres or deliberately included in products like body washes and hair gels. Because so much waste plastic is microplastics, much of the plastic waste that is all around us polluting our world is invisible; or at least until you look through a microscope. One research group from Plymouth did just that, and were surprised to see a sand sample littered with tiny coloured specks – microplastics[7]. Although they are called “micro”, there is no agreed convention for the sizes of microplastic particles, making it impossible to measure how much of it there is out there or compare findings between different groups. This is partly because as microscopes get better, we can see smaller and smaller pieces of plastic.

Another plastics problem is POPs, Persistent Organic Pollutants, which include the infamous DDT. These materials are sparingly soluble in water but very soluble in lipids like plastic ...or body fats. They are highly toxic and carcinogenic, and will accumulate and concentrate in plastics if they find their way into the ocean. We're not sure about the levels of POPs in plastics, nor how levels build up in items that have been in the ocean for a long time, but we do know that, if consumed, the POPs move from plastics into the body fats of the animal until there is the same amount in both. As microplastics are very small, they are even more likely to enter the food chain than bottle tops and other plastic pieces eaten by birds, because microplastics may be consumed by accident. Lugworms, for example, are totally indiscriminate eaters and will ingest anything small enough. Even if the plastic particles have passed out of the lugworm’s body, when a fish eats the worm, POPs that have been absorbed into the body fats of the lugworm will get passed on to the fish and build up. And when we eat the fish... they get passed on to us. Because microplastics are too small to see, we don't know how often this is happening or how much microplastics are exacerbating the problem.

Learn more about The impact of microplastics on sea animals.

3

3

There's some good news. There are kinds of plastic-eating bacteria that biodegrade man-made plastics, found both in landfill sites and, more recently, in the open ocean. Only recently discovered, how fast they act or what products the plastics are broken down into (and whether they are safe or useful) is still unknown[8]. To understand the impacts of biodegradation products, the entire ecosystem has to be considered. We don’t even know what these bacteria really are: DNA profiling has shown them to be closer to cholera bacteria than the kinds of bacteria normally found on seaweed. On the other hand, plastic-eating bacteria may explain the lower-than-expected recorded levels of plastic waste in the ocean and open new questions about what waste products we should be looking for.

We can’t just rely on plastic-eating bacteria to rebalance the waste problem, so scientists are working at developing future plastic solutions. With plastic used in everything from the internet to clothing, eliminating it is unviable - so future designs focus on finding alternatives or redesigning their life cycles.

Currently, bioplastics account for 1% of plastics. These tend to be made from biodegradable renewable plant products that replace the petroleum fraction. Many are only partial replacements, such as bio-PET: polyethylene terephthalate, made from 30% monoethylene glycol, a by product of the sugar industry. Whilst first generation bioplastics were disposable, composting quickly, scientists are now looking into things that last longer but age gracefully, are durable, renewable and recyclable: designed with life cycle of multipurpose applications before finally going to compost. But how these changes are viable chemically and how behavioural changes in users can be altered is yet to be determined.

Perhaps the plastics of the future will be durable, and with the help of the natural world we’ll be able to break them down when they do get out there. In the meantime, we need to keep monitoring what we’re putting out into the environment, how this affects us and other living things, and face the mystery of what lies down at the ocean depths.

This article was written by the Things We Don’t Know editorial team, with contributions from Ed Trollope, Ginny Smith, and Rowena Fletcher-Wood.

This article was first published on 2019-08-21 and was last updated on 2019-08-21.

References

why don’t all references have links?

[1] Billingham, N., University of Sussex, Polymers and their Environmental Degradation, Royal Society of Chemistry Environmental Chemistry Group Bulletin(July 2014)

[2] Fletcher-Wood, R.L., Ball S., Plastic debris in the ocean - a global environmental problem, Royal Society of Chemistry Environmental Chemistry Group Bulletin (July 2014)

[3] Cozar, A., et al., (2014) Plastic debris in the open ocean Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111(28):10239-10244 DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1314705111

[4] Billingham, N., University of Sussex, Polymers and their Environmental Degradation, Royal Society of Chemistry Environmental Chemistry Group Bulletin (July 2014)

[5] Allsopp, M., Walters, A., Santillo, D. and Johnston, P. (2006) Plastic Debris in the World’s Oceans. Greenpeace, Amsterdam.

[6] Law K. L., et al., Plastic accumulation in the North Atlantic subtropical gyre, Science (2010) 329, 1185-1188

[7] Thompson, R., School of Marine Science and Engineering, Plymouth, Plastic debris in the ocean - a global environmental problem, Royal Society of Chemistry Environmental Chemistry Group Bulletin (July 2014)

[8] Zaikab, G.D., (2011) Marine microbes digest plastic Nature DOI:10.1038/news.2011.191"

Blog posts about plastics

Recent plastics News

Get customised news updates on your homepage by subscribing to articles