Extinction

Article curated by Ginny Smith

Extinctions are important events in the history of the earth. By studying fossils, scientists are trying to answer questions about how past species died out, with the long-term hope of preventing us from coming to a similar fate. Understanding the causes of extinction can also help conservation efforts to preserve the incredible diversity of species currently on the planet as far as possible.

Undiscovered species

One species we don't see a lot of is fungi. Many fungi exist beneath the ground and can extend for miles unseen. They are highly diverse and scientists estimate there may be five million fungal species are alive today, but we've only identified 100,000 species. Due to habitat loss, are losing as many as 6 for every 1 plant lost to extinction, but we have no real idea how many we're losing. It's important to know how many fungi there are and how fast we're losing them in order to conserve them.

What causes extinctions?

There are some cases where it is clear why a certain animal became extinct. Dodos, for example, were hunted to extinction by humans because of their large size, tasty meat, and inability to fly, and their habitats were disturbed by dodo-egg-eating rats we brought with us on ships. In other cases, however, it is less clear why an animal didn't survive.

Woolly mammoths lived on an Arctic island until as recently 1700 BC, but it isn't clear what killed off this last group of survivors. It could have been human hunting, although there is little evidence of it left behind. A virus might have led to their demise, or it could have been a change in the habitat, or a large weather event. Alternatively, it could be that the island habitat just couldn’t support them, so as the ice bridge to the mainland melted they became stranded and could no longer survive.

2

2Lemmings are a particularly anomalous species when it comes to survival. Whilst the lemming mass suicide story is a myth perpetuated by the 1958 Disney documentary ‘White Wildnerness’, in which lemming mass suicide was staged in a non-natural environment using cinematic effects and imported lemmings, they do experience weird population cycles. Every four years their populations peak, after which large numbers of lemmings migrate, and many of them die in unfamiliar environments. As a consequence, population numbers drop so low that they risk extinction. Why a more steady population doesn’t establish itself is unclear, although some biologists think predators (in particular, stoats) may have something to do with it.

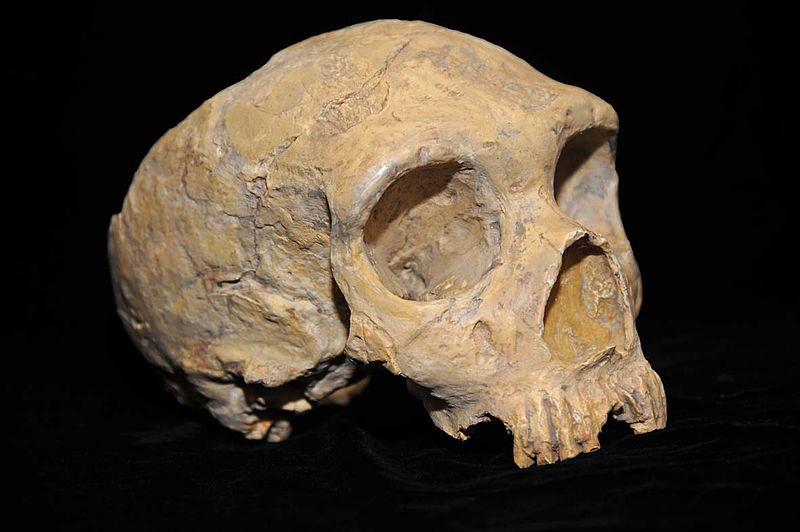

So what happened to this robust and successful species? Some people argue that modern human's increased intelligence meant they could out-compete the Neanderthals. Others argue that they were absorbed into our species as Neanderthals and modern humans met and interbred. People in Europe, Asia and New Guinea have 2.5% Neanderthal DNA, supporting this theory, although it isn't clear that this amount of breeding would be enough to wipe out the species entirely. Climate could have played an important role, as it was very unstable at the time they died out. What is certain, is that more research is needed to find out exactly what happened to the Neanderthals.

2

2Humans extinction

It may be scary to think about, but the likelihood is that one day, humans will no longer exist here on earth. What it is that leads to our downfall, however, is not clear. While there is a chance that it will be something we have done that causes our demise, there are also natural events that could mark the end.

One thing that could wipe us out would be a meteor strike. Millions of meteors appear in Earth’s atmosphere every day, but only a few over the course of a whole year are large enough to be potentially dangerous. NASA should be able to spot the risk early, giving us a significant warning of the danger. But if we did spot a potentially life-threatening asteroid hurtling towards the earth, is there actually anything we could do to divert it? Many scientists are currently working on methods for deflecting asteroids, but whether they would work in practice (and whether different ideas would cooperate) still remains a mystery.

2

2We know it's possible to survive a mass extinction: just look at the birds. One of the few species to survive the mass extinction that killed off the dinosaurs 65 million years ago, a theropod, became the birds we know today. Whilst there must be a biological or ecological reason for their survival, however, scientists are stumped. Lack of other "straggler" species suggest it wasn't random chance that led the birds to persist, and this makes their survival especially exciting and intrguing. It could even help humans.

2

2

Protecting our planet's diversity

By understanding how and why species go extinct, we can better conserve those animals and plants currently sharing our planet. One area of study is how diversity differs in different regions of the earth. We know that some areas are home to a multitude of different species, while others can only support just a few, but the time and resources required to fully explore these differences mean there is still much work to be done.

2

2Of particular interest is extremophiles. Extremophiles inhabit the most extreme and uninhabitable places on earth – and thrive there. In pockets where extremophiles live, such as glaciers, there are often very few living creatures, but rather unique ones. In recent years, changing climate has led to loss of some of these extreme habitats and extinctions of the extremophiles that live there. Scientists who have been tracking these environments have made a rather worrying discovery: that whilst changes such as warming and melting glaciers makes habitats more accessible and so increases the number of species living there, it drastically reduces diversity. Whilst we don't know what role extremophiles play in our planet's health, the loss of so many species is a concern.

3

3This article was written by the Things We Don’t Know editorial team, with contributions from Ed Trollope, Cait Percy, Johanna Blee, and Rowena Fletcher-Wood.

This article was first published on 2015-08-27 and was last updated on 2019-06-06.

Blog posts about extinction

Recent extinction News

Get customised news updates on your homepage by subscribing to articles